List of Unconfirmed and Theoretical SEO Ranking Factors

We've all seen the lists of everything we know are search ranking factors. From Backlinko's mega-post to combing through Google's blog, it's easy to write about what's confirmed.

Where it gets tricky is talking about the search ranking factors that may or may not be real. The theoretical factors, the factors that marketers will swear by, but which Google denies or refuses to discuss at all.

I put together a list of these factors, and I wanted to go through them and discuss whether or not there's any evidence that they're real, or if they're blown out of proportion, or if they're superstition. You might be surprised about what is and isn't real!

If you can think of a ranking factor that I didn't include, something unconfirmed and worth discussing, feel free to let me know in the comments, too.

Now, let's get right to it.

Domain Age

This one is, surprisingly, a bit of a myth, but it has a nugget of truth to it.

The idea is that the older your domain is, the better you'll rank. On the face of it, it seems borne out by the search results, right? After all, tons of domains ranking at the top for nearly every query are years and years old.

There are a few things going on here.

One is that a site that has been around longer has had more time to improve and work on marketing, building up confirmed SEO signals like backlinks.

Another is survivorship bias. You don't see the old sites that aren't ranking, because they aren't ranking. Duh, right?

There's also a bit of misinterpretation here with the so-called Google sandbox. When a new site is created, Google will "quarantine" it, in a sense, putting it in a sandbox and playing around with showing it to people to see how they prefer it. This generally only happens for the first few months of a site's existence; after that point, it settles down and starts from the same floor as everyone else.

Some marketers try to get around this by intentionally buying older domains, but Google's hip to that strategy. Any significant change to the site can "reset" this quarantine until they decide whether or not the site is worth keeping its place. Usually, it's treated more or less like a new site.

Domain Registration Length

This one is an interesting one.

When you go to register a domain name, you generally pay for it for a year at a time. Most domain registrations are pretty cheap, so dropping $12 a year to keep up the site is no problem.

But what about pre-paying for more in advance? Some domain registrars allow you to register the domain for two, three, maybe up to five years in advance. Some allow even longer.

The theory is that if you're confident and invested in your site, you'll register the domain for an extended period. This helps you ensure you don't lose control of the domain, and shows a little bit of confidence that you're going to keep the ball rolling.

This is all backed up by a patent Google owns. The patent backs up the theory that good sites and trustworthy site owners are more likely to pay in advance, while scammier and low-tier pages are more likely to register for just a year at a time.

Now, Google owning a patent doesn't mean they actually use that technology. Patents are a big weapon in corporate warfare, and by patenting something like that, Google can keep other search engines from using the same technology or force them to pay to use it.

In this case, there's no real reasonable way to test whether or not domain registration length is a valuable search factor without already having an established site that you change nothing about except extending your registration. If any of you have that and want to give it a try, let me know!

My assumption is that if Google pays attention to registration length at all, it's just to make sure that, if your domain is about to expire, they can take action if it's bought out from under you and replaced by a phishing site or other malware. Realistically, though, even if it is a ranking factor, it's so incredibly minor as to be inconsequential.

Still, I would say it's worth registering your domains for a longer length of time just as a security measure. Be proactive in securing your registration and avoid the chances of having it parked out from under you.

Exact Match Domains

Exact Match Domains are domains that are an exact match of the primary keyword the site is trying to target. If you think people are searching for pest control in Albany, you might make your site www.pestcontrolalbany.com to target it.

This was a thing, many years ago, when Google was much, much simpler than it is now. But, it was heavily used as a spam technique, where a company might make hundreds of these local EMDs and pretend to be hyper-local, or otherwise try to weaponize an EMD for short-term benefit.

In 2012, or thereabouts, Google put out the EMD Update, which basically penalized any site using an EMD that wasn't high quality. A lot of marketers at the time decided this meant EMDs were dead, and changed domain names and avoided them ever since.

These days, there's no penalty for using an EMD as long as your site is relevant and high quality. There's an implicit penalty to it in that you don't have a solid branding attached to an EMD in 99% of cases, but that's minor and more social than algorithmic. Bad sites can be penalized for having EMDs, but bad sites are going to be penalized in a dozen ways, so that's hardly saying much.

I wouldn't call an EMD an advantage these days, but it's not a disadvantage out of the box.

EDU and GOV Value

Another persistent SEO myth is that when it comes to backlinks, getting links from .edu and .gov sites is better than links from .com, .org, or other TLDs.

The idea comes from the fact that these are restricted TLDs. To make a .edu website, you have to be a registered educational institution. Likewise, .gov domains can only be made by government entities. Higher quality guaranteed by filtering indicates that the links should have more value, right?

In fact, if anything, it's actually the opposite.

For one thing, the people who run these sites aren't necessarily any better than the average .com site owner. For another, there are plenty of ways to get links from these kinds of sites that aren't actually reputable or authoritative.

Google does a ton to evaluate the relevance, context, and relative value of links. They could assign more value to a link from a .edu or .gov site, sure. But, more often, because these kinds of sites are frequently spammed, Google actually tends to ignore their links more often. John Mueller said as much.

Bing, on the other hand, does pay more attention to them.

The Google Sandbox

I mentioned this above, but it, too, is an unconfirmed element of SEO.

To reiterate, the Google sandbox is the idea that new sites are put into a temporary quarantine while Google makes sure it's a legitimate site and not some spammy, algorithmically-generated garbage meant to capitalize on short-lived trends or newsjacking, then cut and run after the viral profits.

It's been a bit of an SEO conspiracy theory for over 20 years at this point. During that time, Google hasn't confirmed an explicit sandbox. But John Mueller has mentioned that it can take time for Google to index and rank your site appropriately.

I think there's a kernel of truth to this one as well, but it's not an explicit sandbox. It's more like a sandbox-like effect caused by layers of anti-spam filtering, the fact that new sites generally have very little to boost them in the rankings right away, and the fact that it takes a while for search rankings to settle.

Google also likes to change things up from time to time, using personalization and other search impacts to vary ranking order, which helps them essentially split-test ranking options and see whether or not the rest of their algorithm is reflected by user behaviors.

Bounce Rate

Bounce rate is contentious as a ranking factor.

On the one hand, it makes sense if Google were to use it as a ranking factor. If people frequently click through to a site and are back to browsing almost immediately, that indicates there wasn't anything satisfying on the site, so maybe it should be ranked lower. Conversely, if they click through and end up spending their time there, it seems like it's a good site that should rank well.

The competing argument is that bounce rate is notoriously obnoxious to track accurately. A long post like the one you're reading now could be immensely satisfying for a user, and they could spend an hour here reading it, but if they don't take a secondary action that triggers a second event in analytics, it can still be recorded as a bounce.

Bounces, as such, aren't necessarily bad, either. A user searching for a recipe, clicking through, writing it down and making it is technically a bounce. A user searching for a factoid on Wikipedia, clicking through to read and closing the window, is a bounce. In both cases, they were satisfied users. Holding that against the site owner doesn't make sense.

Some studies show a correlation between bounce rates and rankings, but it may be very contextual across different kinds of sites. Also, since it's not necessarily data that Google has complete access to (such as what about people who don't use Chrome, and sites that don't use Google Analytics?), it might be minor at best.

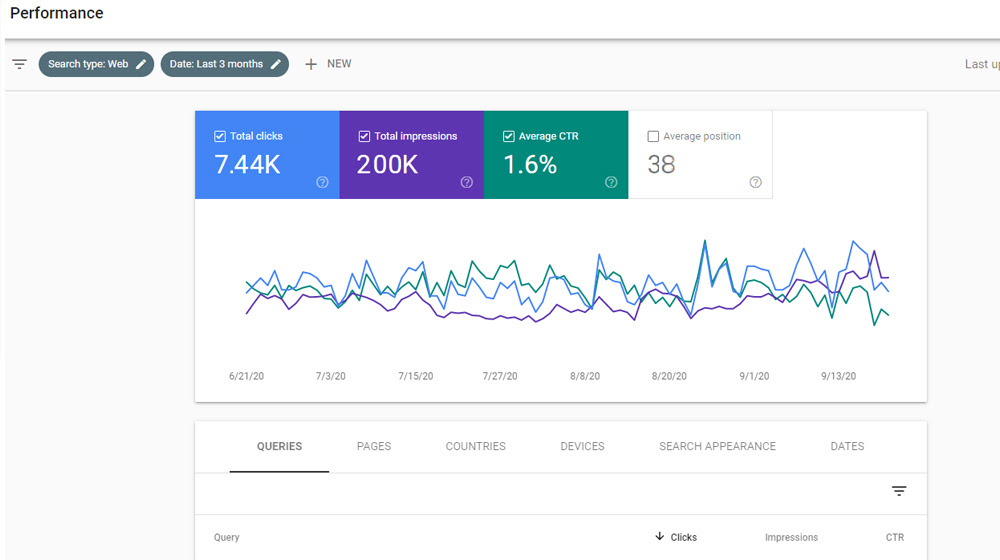

Click-Through Rate

Does click-through rate affect your search rankings?

Well, first, you need to define what kind of click-through rate. Are we talking:

- Clicks from Google's organic search to sites?

- Clicks from paid Google ads to sites?

- Clicks from links from one site to another, monitored by Chrome?

- Clicks from secondary knowledge boxes and AI Overview citations?

The fact is, there are a lot of different forms of CTR, a lot of different ways of tracking it, and a lot of ways that a click might not be the most relevant outcome. At times in the past, Google has said that a higher organic CTR might boost rankings a bit, and other forms of CTR might feed into the nebulous "RankBrain" AI Google has been using, but it's all unconfirmed as a major ranking factor.

The way I see it, CTR is less of a ranking factor and more of a reward for other ranking factors improving. CTR itself might not tangibly help your rankings, but the things that come along with higher audience levels can feed back into it.

Do you get a ranking boost when your site is shared more on Facebook?

Google says no. I say that's a good thing.

Social media sites already have their own algorithms for surfacing content. Making the social shares you get on a social network like Facebook have an influence on search ranking would hand those sites a lot of power.

Picture this: if more retweets on Twitter got a site ranked higher, do you think Elon would even hesitate before implementing some astroturfing to boost sites he likes, or that pay him? I doubt it. Same with Zuckerberg and Facebook, which has been caught gaming algorithms several times in the past.

I suspect that Google wanted to use social signals as a ranking factor at some time in the past, but their experiments with things like the Twitter Firehose put the kibosh on it pretty quickly. It's too easily manipulated and has too little meaning behind it.

That said, using social media, getting social shares, and getting more social clicks does benefit you… on those social networks. So, it's not something to ignore, just not something that Google is going to incorporate into their algorithm.

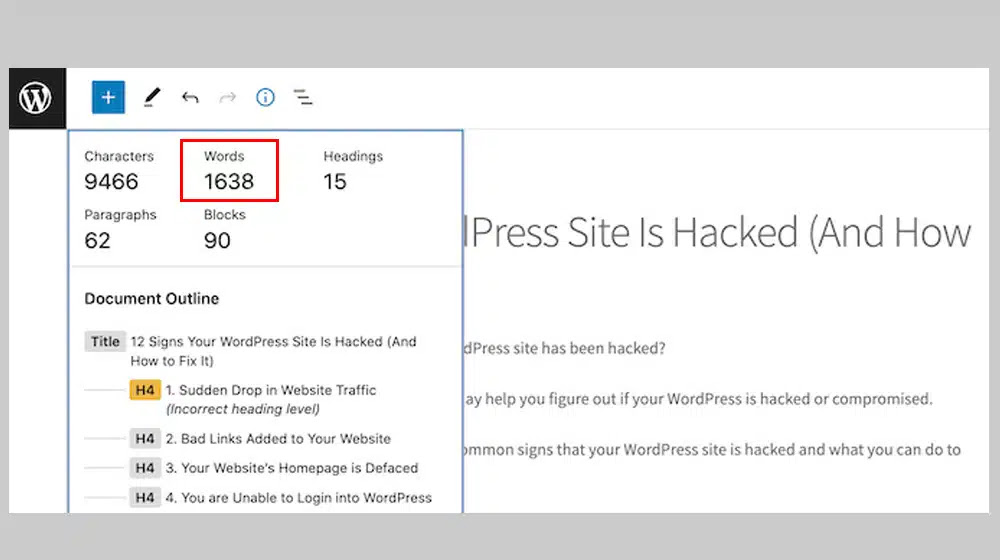

Content Word Count

Does the length of your content help?

Google has stated as firmly as they can that it is not a direct ranking factor. You can't just add more words to a page and get a higher ranking because of it.

The myth that word count is important comes from roughly, oh, say, 2011, with the Google Panda update. That update penalized thin and duplicate content. "Thin" content was loosely defined and, among other things, included content that was too short to be valuable.

I'm no stranger to writing long content, but I've also worked with sites where the average length of a blog post is under 400 words, and they do fine. Maybe they would do better with longer posts, but if so, that's not because of the word count.

Why are longer posts more likely to rank better? They just have more space to cover more topics, give more information, and generally be more useful. There are only so many keywords you can use in a 400-word post compared to a 2,000-word post, you know? The more space you have to build value, the more value you can build, and the better you can rank based on that value.

Keyword Density

The concept of keyword density was all the rage for a while.

The concept of keyword density is simple: what percentage of words in your content are keywords? That can be a reasonable metric to watch, and it's not exactly an optional metric either. It's impossible to write content without keywords, because foundationally, keywords are just words.

The SEO conspiracy is that there are "sweet spots" for keyword density. Too low a keyword density and you're somehow lacking in relevance, and Google can drop your ranking because of it. Conversely, too high a keyword density and you could be penalized for keyword stuffing.

There are a few reasons why this idea picked up steam.

- Keyword stuffing is real and can definitely get a site penalized, though most of the time it's related more to hiding keywords, stuffing keywords in footers and other areas, or having such a high density that the content is barely readable.

- Some people noticed that if they added more keywords, their performance could increase (likely because they were using new or variation keywords, before semantic indexing).

- Matt Cutts once said that increasing keyword density had "diminishing returns," which meant that there would be a point where density was optimal.

Modern studies have shown basically no correlation between ranking and keyword density, though. Adding more keywords is good if you can add more relevant keywords, but if you're adding them just to boost the density, it's not doing anything except maybe making your content look less natural.

The fact is, these days Google is extremely good at understanding what a page is about, and you don't need to repeat keywords a dozen times a page to hammer it home.

Content Freshness

This is an interesting one because there are some elements of truth to it, but also friction with other factors.

If Google prioritizes new content over old content, why would they also prioritize old domains over new ones?

The myth here is not that Google likes fresh content; it's that Google always prefers fresh content.

Content freshness is important for certain kinds of queries and information. For others, it's not very relevant. If you're writing about a historical topic that doesn't change over time, there's no reason to continually update that content, and new coverage of it isn't going to bring anything new to the table.

Conversely, there are plenty of queries that deserve freshness when they're about current events, news, changing data, and similar topics. There are plenty of reasons to update certain kinds of old content, and reasons why newer, more updated versions of older content can outrank the older and more established content. It's just not a 100% guarantee that updating content makes it better.

Unlinked Mentions

Also known as implied links, this is when you mention a brand, but you don't link to it in your content. By mentioning the brand name, the tacit link is there, but there's no explicit hyperlink, and thus nothing for Google's ranking to latch onto and track.

What if Google could track those implied links and give them weight similar to actual links? After all, if you're willing to mention the brand by name, that's nearly as good as dropping the link, right? And when SEOs are worried about link density, too, it makes sense to be picky.

This is, once again, one of those SEO things that comes from a Google patent. They patented a method for evaluating implied links on a similar basis as real links. But there's no evidence that they actually use that patent.

Unlinked mentions do matter, in terms of building awareness and authority, but they're unlikely to be a direct ranking factor. Instead, they feed into authoritativeness and similar reputational metrics, which feed into user behavior, willingness to give actual links, and other, stronger factors.

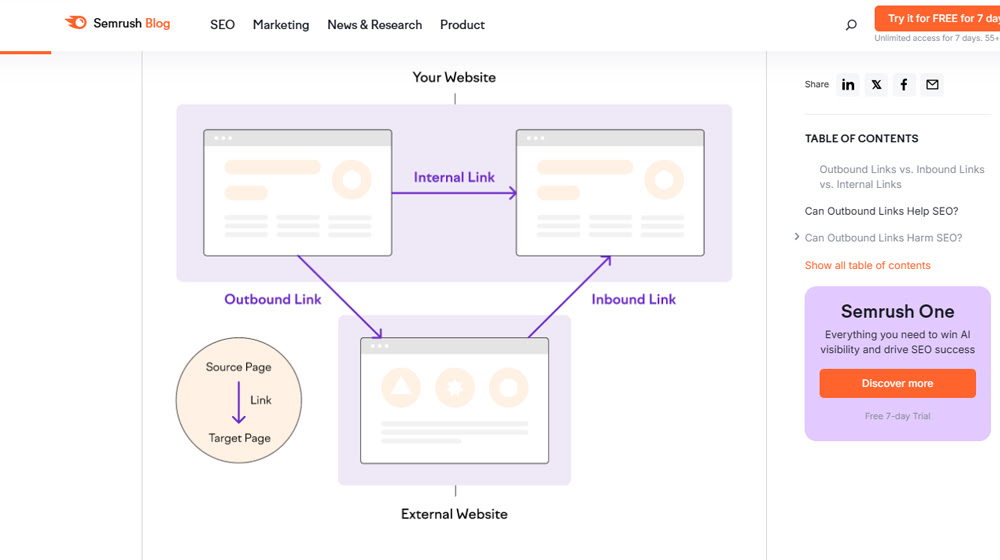

Outbound Links

This one is an odd one. The idea is that by linking from your site to an authoritative site, you get some benefit.

There's a tiny, tiny kernel of truth in this, but not in the way you might think, and it's very much not something you can use or optimize for.

When you create a piece of content, it's going to work better if you have trustworthy citations. This is especially true in high-standard fields like medicine, health, finance, and other YMYL topics. It's a lot less true for lower-standard fields.

This isn't direct. You can't add more citations and get a ranking boost because of it.

Adding outbound links is also a way to tit-for-tat link exchanges in a natural way. Good sites are marginally more likely to link to you when they see you've linked to them. But, only marginally.

Interestingly, even Google's AI Overview claims this one is really a ranking factor, citing things like links building trust, helping Google understand context, and boosting the user experience.

You'll note that none of those are direct ranking factors. Don't trust the AI overviews blindly, folks!

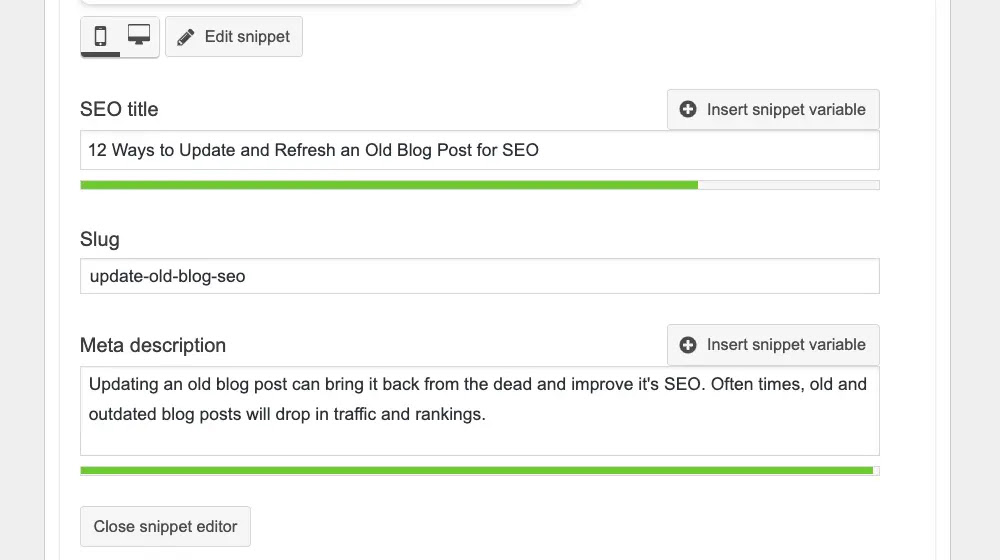

Meta Descriptions

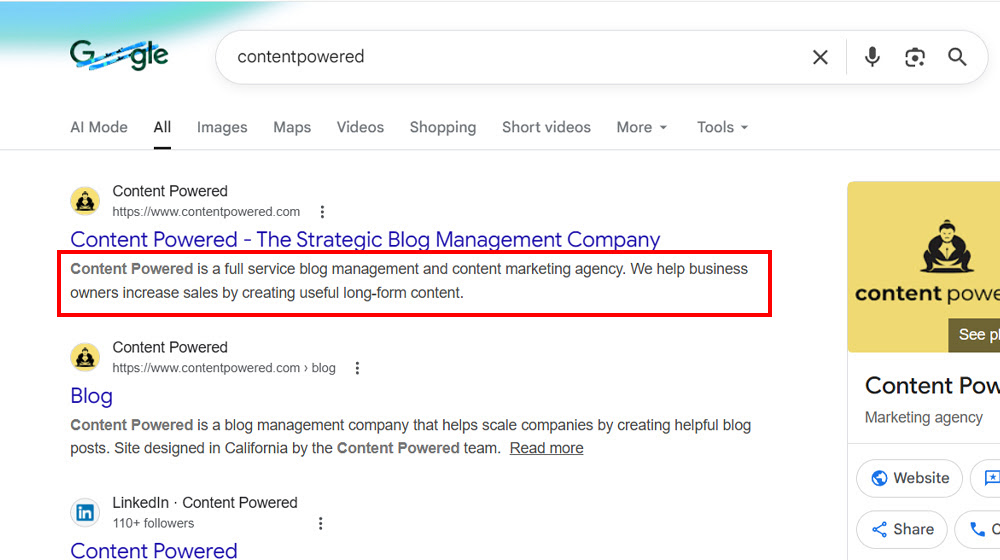

Long considered one of the core elements of meta SEO, the meta description is data you specify to show up beneath your link in the search results. It's a place for keywords and adequate descriptions of the content, to help users decide to click.

Personally, I think they're on the way out.

As content gets longer and longer, it's harder and harder to adequately supply a review of what's in the post in just a few hundred characters.

A while back, I did a light study and found that just 17% of sites in the results pages used the meta descriptions provided. For the rest, Google just picked a relevant passage from the page and made their own.

Meta descriptions aren't a direct ranking factor. They exist for CTR purposes, and while CTR has some potential (as discussed above), the presence or content of the meta description field is not nearly as relevant as people think.

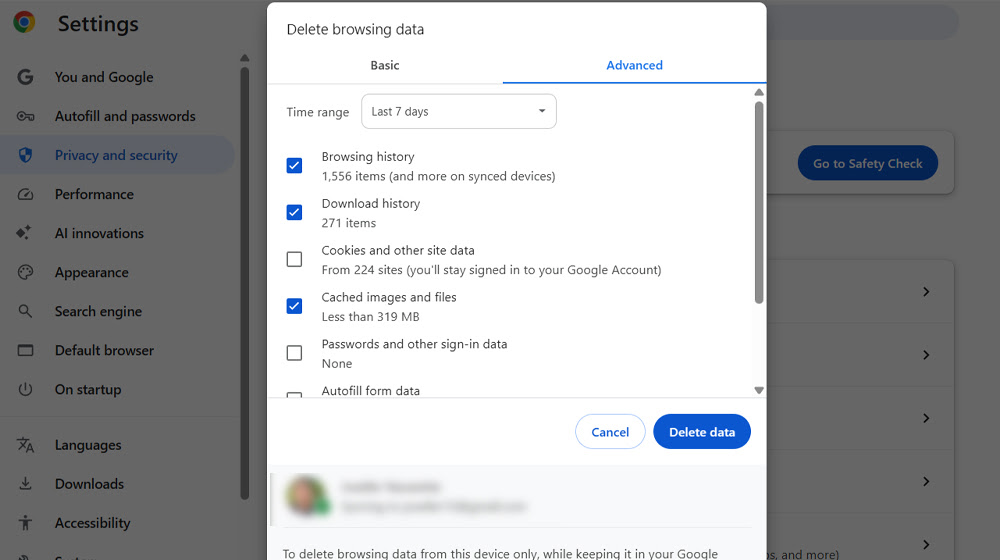

Chrome Data

Google, being the company that owns both the search engine and the web browser, is rife with potential to cause problems, and one of the conspiracies that cropped up is that Google snoops on Chrome users, gathers their data, and uses that data in its ranking algorithms.

We know that Google uses Chrome data for some things. It's low-key part of their indexation and discovery, it can help them with telemetry and data on site speed and other potential usability problems, and so on. But Google has said before that they don't use Chrome user data in its ranking.

Except, in the recent DOJ vs Google trial, Google has been forced to disclose some things, including the fact that a lot more user data is used in a lot more ways than was previously discussed.

From conspiracy to confirmation, I guess. The trouble with knowing this, though, is that you can't exactly do anything about it. What are you going to do, make Chrome-specific enhancements to your site?

Clarifications and Misunderstandings

There are a bunch of other things that float around in SEO circles that are often discussed as search ranking factors or penalties, but most people have some misconceptions about them. The end result may be the same, but the reasoning may be different, which can lead to drawing the wrong conclusions and shying away from valid strategies. So, I figured I'd dedicate a section to giving each of these a little bit of attention.

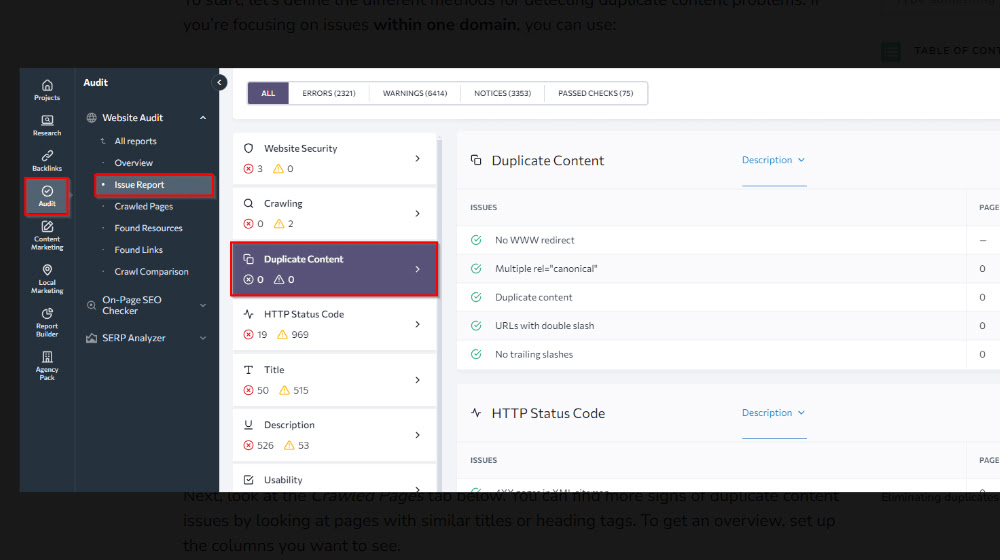

Duplicate Content Penalties

First, duplicate content. Panda made duplicate content a bad thing, but that brings up a lot of questions. How close is close enough to be duplicate? What about legitimate cross-posting between, say, your site, your Medium, your Substack, and your LinkedIn? What about validated syndication?

The fact is, duplicate content isn't a penalty; it's a filter. That's what canonicalization is for: to tell Google which version is the one to rank. The others exist for users, and that's fine. Google won't hold them against you. The "penalty" comes from if you specify the wrong one or don't specify at all, and your main site gets filtered instead of the syndicated copies.

The only penalty you'll get is for content theft, and that's a whole other can of worms.

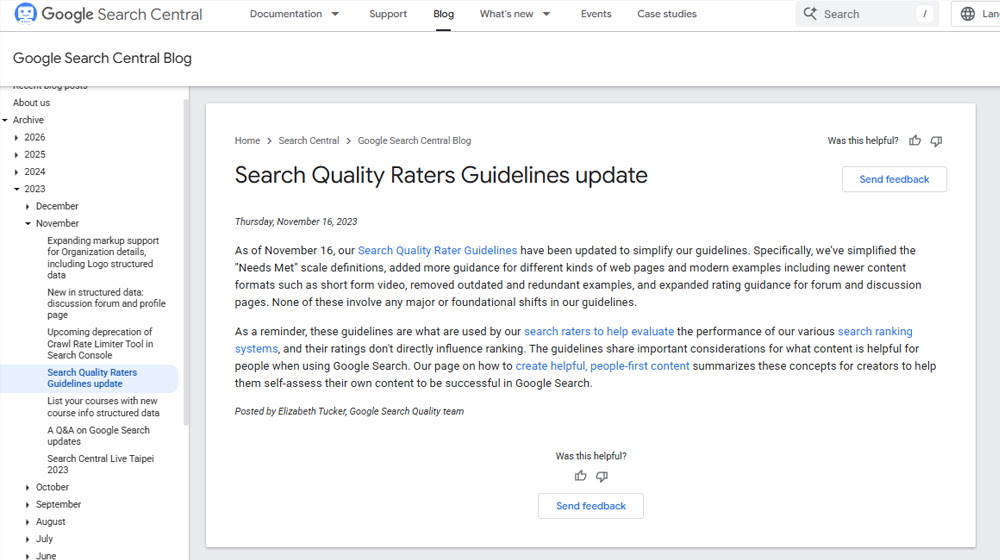

E-E-A-T

Expertise, Experience, Authority, and Trust: the pillars that make a site reputable and useful. Often, EEAT is discussed as if it's part of Google's ranking algorithm, but it's actually not. But that doesn't mean it doesn't matter.

Google employs a legion of freelancers called "Search raters" whose job is to read a huge document of guidelines and then, when given search results, rate the sites on them for their viability and position. Among those many guidelines are ways to evaluate the trustworthiness and authority of a site, which comes down to EEAT.

Google has promoted EEAT as a way to gain ranking and growth, but it's a third-order factor that isn't directly part of the algorithm, but is more fed into systems that feed into systems that feed into the algorithm.

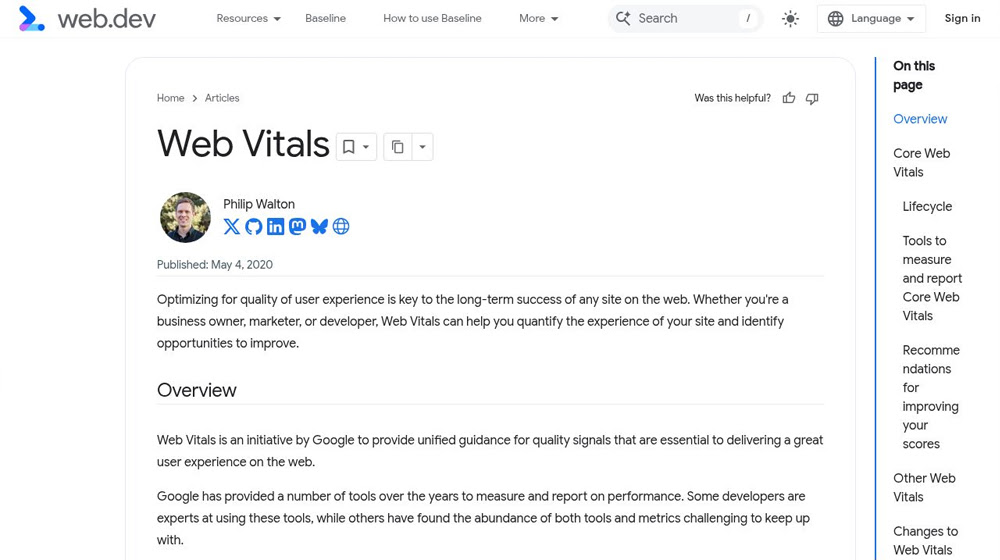

Core Web Vitals

Core Web Vitals is a set of three metrics that evaluate certain ways a site performs.

These metrics include:

- Largest Contentful Paint: how long it takes for the main content of your page to load.

- Interaction to Next Pain: how long it takes between a user click and the site responding.

- Cumulative Layout Shift: how much the content of a page shifts as other elements load.

Google has made a pretty big deal out of these, but they're actually a minor factor in the algorithm. Improving your web vitals isn't going to make you shoot up the rankings, but it can make you edge out a competitor when you're neck-and-neck.

HTTPS

Use SSL security. Google made it a ranking factor (it's a very small one), but really, it's 2026.

SSL is cheap and accessible, and it's part of robust online security. There's no reason not to use it, regardless of its impact on SEO.

301 Redirects

Page value is tied to the URL. When you need to change URLs, you need a redirect, usually a 301 redirect. But, historically, even that dropped a huge amount of page value. Some passed along, but it was a massive drop, which made changing URL structures, site reorganizations, rebrandings, and domain changes very challenging.

These days, the penalty for a 301 is a lot lower. It's still there (especially if the redirect ever disappears), but a lot of the loss is just in the eventual broken links. Most of the value transfers or can be recovered.

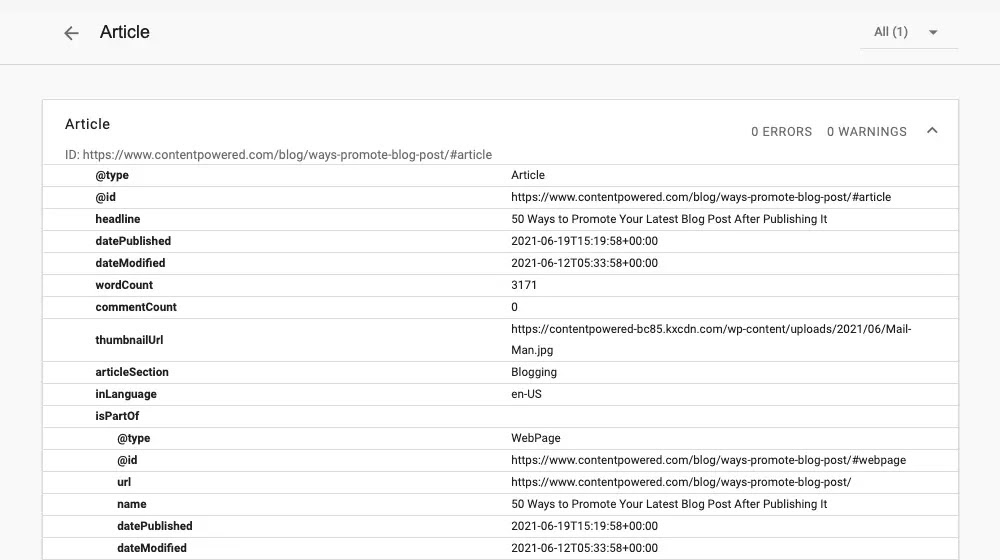

Schema Markup

Schema markup is metadata that is used solely by the search engines to understand more about a page. Some of it helps with, for example, shopping results, to make sure SKUs, prices, and other data are appropriately flagged. This helps prevent cases where a SKU is misidentified as a price, and the search results list a $5 item as costing $54874928, or whatever.

Other data is used for the rich search results. If you search for a food recipe and get that box with reviews, time, and ingredients, that's all pulled from the Schema data.

Schema markup, contrary to popular belief, is not a direct ranking factor. It's a search enhancement. Again, this can boost CTR and make the site more attractive, but it's not directly affecting your ranking.

So, there's my list. Is there anything you think should be added to it? If so, feel free to leave it in the comments, and we can discuss it there, or I can add to the post over time.

Comments